- Home

- About

- Inkflower

-

Books & Writing

- Inkflower

- Arabella's Alphabet Adventure

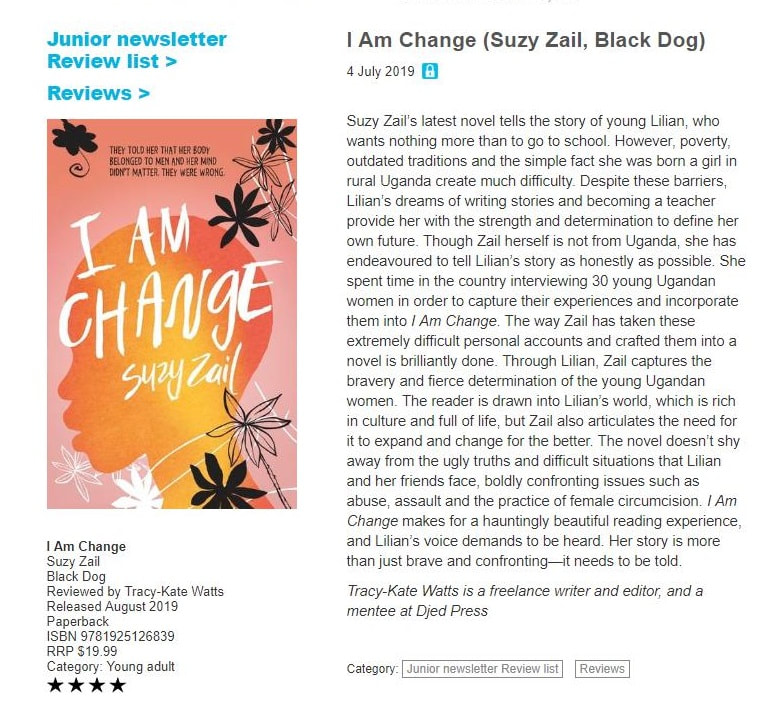

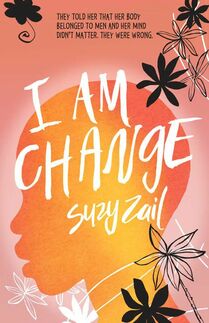

- I am Change

- The Wrong Boy

- Alexander Altmann A10567

- The Tattooed Flower

- Playing for the Commandant

- Hanna Mendels Chans

- La Pianista di Auschwitz

- Der Klang Der Hoffnung

- De Gave Van Hanna Mendel

- Saving Midnight

- Was Dir Bleibt, Ist Dein Traum

- Il Bambino Di Auschwitz

- Smitten

- All You Need is Love

- Pianista De La Auschwitz

- Other Writing

- Author Talks

- Contact

- News

|

Thrilled to be among this stellar group of Australian writers selected by Australia's independent booksellers for the Indie Book Awards 2020 young adult long-list! Shortlist to be announced mid-January!

3 Comments

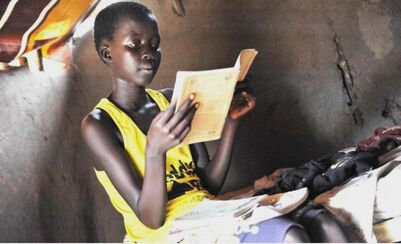

Lilian pulled a book from her bag and cradled the ragged paperback in her hand. “It’s like slipping inside someone’s skin,” she whispered. “You can be anyone. Do anything …” Lilian so badly wanted her father to understand. But how to explain that being in the middle of a story was like being everywhere and nowhere at the same time? - I Am Change Growing up in Australia, I stepped into the magic of stories every day, shedding my skin to try out different lives to test who I might be. In novels I discovered that girls could be heroes. And the more I read the larger my world grew. I had stories to make sense of the universe, atlases to reveal whole continents to me and dictionaries to add to my collection of words. For too many girls in Uganda, books are a luxury. “Books,” they told me, “are more than just things made of paper and ink.” To turn the pages of a book meant gaining a vocabulary. It meant mastery of the English language and that meant a job. Which meant quieting their growling stomachs and paying for their siblings to stay in school. I saw their eyes light up as they turned the pages of picture books and tattered paperbacks. And I saw them hug the books to their chests before handing them back to their teachers. They were used to returning books. “We aren’t allowed to take them home,” they explained. Their classrooms and school libraries - if their school had a library - were often almost empty, the books too few to be given out on loan. I didn’t ask if they could afford to buy books; they couldn’t afford lunch. And they were the fortunate ones, the girls who were still in school and hadn’t been married off. Of the thirty girls I met in Uganda in 2015, only six had made it to high school, all of them on scholarships. Most were orphans. They lived in concrete boxes in the city’s slums, walking an hour to school on an empty stomach and they considered themselves blessed. They were lucky to be learning, they told me. “If you can read and write you can get a good job and you won’t be hungry.” Every bit of knowledge they could wring from their teachers and from books was a step away from the slums. I asked the girls what made them smile. There was so many sad stories, I wanted to know what brought them happiness, because they were so much more than poor. They were fierce, determined, warm and generous. And they were hungry to learn. “Light bulbs,” they told me. “A second pair of underwear. A pair of shoes.” But mostly it was books. Books were their escape, not just from a difficult day, but from a hard life. I talked to girls who walked through the bush to get to school, risking sexual assault and their rejection of their families; girls who sat cross-legged on the dirt floors of their classrooms while their brothers sat at desks; girls who sold their bodies for textbooks and washed their neighbours’ clothes to pay for excursions. Reading wasn’t just about being transported to a different time and place. For the girls in the slums and villages of Uganda, books were their ladder out of poverty, a passport to a better life. Because it’s hard to escape abuse if you can’t read and write. So what can we do? We can give girls books. When I posted #giveagirlabook on @authorsuzyzail a few months ago, calling on people during Book Week to spare a thought for the millions of girls who dream of owning a book, the response was impassioned and immediate. People wanted to give their pre-loved books to girls who couldn’t afford them. I just had to find a way to get their books to Africa. And that’s when I discovered Australian Books for Children of Africa, a non-profit organisation who ship books to impoverished schools. To date, they’ve sent over 250,000 books to empower children through education. And now that we’ve teamed up with them, we can get girls in Africa precious picture books, novels, dictionaries, history books and atlases. Click HERE to find out how to donate your new or second hand books to girls who can’t otherwise afford them and mention #giveagirlabook to earmark your donation for girls in need. Those books your kids read that they’ll never re-read? Donate them. The childhood books you keep boxed up in the garage because you can’t bring yourself to throw them out? Let a girl in Africa turn the pages in wonder as you once did. If you’re a member of a local library, find out what they do with their old books. Your child’s school? They have to cull their library collection every year. Send them the link. We might not have the power to change the world, but we can change one person’s world…starting with a book.  AUTHORS EMPOWERING GIRLS: WE SPEAK WITH SUZY ZAIL, AUTHOR OF 'I AM CHANGE' Welcome to the second interview in our 'Authors Empowering Girls' series! We love empowering books for girls so much that we're speaking to the amazing authors who wrote them. This month we're speaking with the multi-talented Suzy Zail, young adult author, about her empowering new book 'I Am Change'. Read Suzy's incredible story below and be inspired by all the amazing work she is going to empower girls around the world. Thanks Suzy! What's the name of your book and what's it about?‘I am Change’ is the sad but empowering story of a young Ugandan girl’s struggle to stay in school. I wrote the book in collaboration with the many girls I interviewed while on a research trip to Uganda in 2015. The heartbreaking and intimate stories they shared have all made their way into this book about a girl who refuses to shrink herself to fit other people’s idea of what a girl is. In Lilian’s small village a girl isn’t meant to be smarter than her brother. A girl is meant to go to school, or enjoy her body or decide who to marry. Especially if she is poor. Tell us a bit about yourself and how you got into writing.I have always been interested in people. When I left school, I wanted to be a psychologist but my father thought Law would be a safer option. Safe is important when you’ve seen the inside of a concentration camp. I completed my degree and practiced for six years specializing in family law but then, in 1998, my father was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease and given 6 months to live. I quit. Life was too short to do something I wasn’t passionate about. I didn’t know what I wanted to be; I just knew that I wanted to spend time with my father. And he wanted the same thing. He didn’t want to waste the little time left to us crying, he wanted to talk and the first thing he wanted to tell us was his life story, so he flew the family to Fiji where we spent 9 nights, over 25 hours, listening to his story. We knew he’d survived the Holocaust as a child, but didn’t know what he’d seen in the camps. We knew he’d lost his parents and brother but he’d never told us how. He told us everything, and his openness in allowing us to share every aspect of his life and later his illness, was the greatest gift he gave us. He told us about his early years, being beaten up at school, the yellow armband, the trip in the cattle train to Auschwitz and his first experience seeing death. He told us about being separated from his sisters, mother, then father and brother. My father hadn’t told us these things because they weren’t part of his new life in Australia, with us. He’d decided after coming to Australia in 1950, that the war had been a bleak time in history and that people were, in the main, good and kind. So he disconnected from the past as a way of moving forward. But now he was dying and it was time to look back…. The 6 months turned into 5 years and watching my father use the time left him as an opportunity to deepen his relationships and grow as a person, I knew I had to pass on the lessons I’d learned while watching him die. Writing his story, The Tattooed Flower bound us together. It also helped make sense of his illness. There had to be some point to my dad dying, some upside. The upside is we parted friends. The upside is I knew his favourite colour and what he dreamed about at night. And then, just before he died, I promised I’d get his book published. I had no idea how to write, at least not creatively, so I went back to university and studied professional writing and editing at RMIT. A year later I sent my father’s story to a publisher and that was the end of my law career and the beginning of my writing life. What made you want to write an empowering book for girls?I think it was fear that drove me. I started thinking about writing a book about girls’ rights around 2014 after Boko Haram, a terrorist organisation opposed to girls’ education, abducted more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls. The kidnapping haunted me. I wondered what I could do. Not just for the hundreds of terrified girls, but for the millions of girls around the globe who were being denied an education. And then, by chance, I met Nakamya Lilian, a 29-year-old Ugandan girl visiting Australia. As soon as she told me her story about growing up in a small impoverished village, desperate for an education, I knew the heart of my next book. But Lilian’s story was only one story, one voice. I needed to learn more, so I flew to Uganda. I didn't know what it felt like to be a poor African girl without shoes or schoolbooks. I needed to speak to girls who did. I interviewed thirty girls through organisations like Concern for the Girl-Child and Girls Not Brides. I went to their villages, visited their huts, walked to the wells where they gathered water and visited the schools where they learned to speak English until, one by one, they dropped out. They told me about forgoing meals to pay for textbooks and trading their bodies for school fees. They told me about the lessons their aunts taught them about their bodies and about men. All of them wanted, more than anything, to learn. It was confronting learning about forced marriages, female cutting, domestic violence and the everyday struggles of so many young girls. But then, in the middle of the heartbreak, were small moments of happiness; young girls smiling and stamping their feet to the beat of a drum, starlight, fire light, cousins and clan. And these brave, fierce girls, determined to learn. I knew this book I was planning to write wasn’t enough to make up for all they’d lost, but, as an author, story was the best way I knew to inspire action, to make people care. Because that’s what books do - especially sad ones - they force us to imagine another person’s pain; to understand, rather than judge, to connect as humans. I didn’t know how I would trap everything I’d learned in that complicated, beautiful place in the pages of a novel but I was determined to try. I was writing during troubling times and that propelled me too. When you’re writing, you’re trying to find answers to things you don’t understand. I didn’t understand how a man who had so little respect for women was elected to run one of the most powerful countries in the world or why women’s rights were being stripped back and racism was on the rise. All that confusion, anger and fear found a home in Lilian, a girl who wouldn’t be tamed. A girl who spoke out and rebelled in ways I never did. I’d grown up always doing as I was told, doing what was expected. And so, I wrote a book about a girl who was afraid, but used her fear to fuel her success. I threw obstacles at her to see if she would make it. I made her stand up and demand what was hers. I wasn’t a particularly assertive or confident teenager, back then we didn’t have the language or framework to tackle inequality, we didn’t have Me too or Michelle Obama and so when my driving instructor made comments about my legs, or the father I babysat for flirted with me, I bristled but said nothing. Writing this book for teens about female empowerment, empowered my own teenage self. As a teen I’d never thought of myself as a feminist. I didn’t know who I was or what I stood for and it seemed like such a big statement, so much more than what it is - someone who wants to shape their own life and believes they matter equally. I wanted Lilian to matter equally. I wanted her to find her voice. I didn’t realise in the process I would find mine. What are your thoughts on strong female characters in books?Love them. And part of the reason I wanted to write about a strong Ugandan girl was so the girls I had met could read about a girl like them. The only books many of them had, if they could afford books at all, were fairy-tales about white-skinned princesses with straw-coloured hair who wore ballgowns and glass slippers. They wanted to see their lived experience on the page and be inspired by girls who had to wake at 4 am to wash the neighbours’ clothes so they could afford to pay school fees. What does girl empowerment mean to you?It means different things depending on where and how you live, but for me it means being able to shape your own life. It means having the right to make decisions about your body, your career and who you live with. It means having equal rights and being encouraged to dream big. And always believing that you matter equally. What's next for you and where can we follow your work?I Am Change has just hit bookshelves so I’m in the process of promoting it - doing talks at schools and trying to raise awareness – and funds – for girls’ empowerment and education. The aim in all my books is to reveal to readers worlds they don’t know. With this book it was to have readers look up from the page and be stirred not just to feel something but to do something. So, on my return from Uganda I set up Help Girls Learn Uganda, an initiative to raise money for the 5 incredible organisations who support the girls who shared their stories with me. I’m also working on a more recent initiative ‘Give a girl a book’, which I launched on Instagram, so I’m busy setting up ways to get books into the hands of girls who need them, whether they be textbooks, picture books or novels. I’m also itching to get started on another novel… and waiting for inspiration to strike. You can connect with me on my website, or follow me on Instagram. You can check out Suzy's fantastic book 'I Am Change' on Amazon or Booktopia. I wish I could've invited everyone to the Launch of 'I Am Change'! It was such a great night. Sarah Ireland, the CEO of OneGirl kicked the night off with a moving speech about the power of educating girls, then after I spoke, Olivia Bamwine, a Ugandan friend of mine, talked about her own experiences growing up as a girl in a male-dominated society where she was taught to stay silent and serve men.

Here's an excerpt of my speech if you're curious about why I wrote the book and what I've learned through the process. It’s been four years since I went to Uganda, three and a half years since I tapped the first words of ‘I Am Change’ onto my keyboard and saw the beginnings of a story fill the screen. I remember how badly I wanted to capture the sticky African heat, the dusty streets and the wide smiles of the girls whose stories I promised to tell. And how huge a task it seemed to trap everything I’d learned in that complicated, beautiful place in the pages of a novel, a novel I hoped might illuminate what it means to be a girl in a place where girls are invisible. Writers are often told 'Write what you know.' In writing holocaust fiction, I’d clung to that rule, drawing on my father’s childhood story to write my first two Young Adult novels. The 2014 abduction of more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls by Boko Haram, a terrorist organisation opposed to girls’ education, changed that. The kidnapping haunted me. I wondered what I could do. Not just for the hundreds of terrified school girls, but for the millions of girls around the globe who were being denied an education. And then, by chance, I met Nakamya Lilian, a 29-year-old Ugandan girl visiting Australia. As soon as she told me her story about growing up in a small impoverished village, desperate for an education, I knew the heart of my next book. But Lilian’s story was only one story, one voice. I needed to learn more, so I flew to Uganda. I was a girl who grew up surrounded by books, a girl encouraged to learn. A girl who'd never felt the sting of a slap, or the hollowness of an empty stomach. I didn't know what it felt like to be a poor African girl without shoes or schoolbooks. I needed to speak to girls who did. The best way to do that, I decided, was to contact aid organisations who fought to keep girls in school. I settled on five organisations based in Kampala who advocated for girls’ rights and emailed each of them explaining that I hoped to write a novel about a Ugandan girl struggling to stay in school, but to write an authentic story I needed to meet the girls who lived that story. I met thirty girls through organisations like Concern for the Girl-Child and Girls Not Brides. I went to their villages, visited their huts, walked to the wells where they gathered water and visited the schools where they learned to speak English until, one by one, they dropped out. They told me about forgoing meals to pay for textbooks and trading their bodies for school fees. They told me about the lessons their aunts taught them about their bodies and about men. All of them wanted, more than anything, to learn. I started my days at 8 am, with a line of girls waiting to share their stories. I knew the power of my novel would ride on detail, and so I asked lots of questions. What were the walls of your hut made of? Could you see the stars through the thatched roof? How do you lift a jerry can full of water onto your head? I had an hour with each girl, so I had to get straight to the darkest parts of their story. I asked questions you’re not supposed to ask a stranger: When you got your period, what do you use to soak up the blood? How did you feel when your husband took another wife? How often did he beat you? I mined their most private and intimate moments and they forgave my ignorance and shared their heartbreak with such warmth and generosity. At first, my tendency was to ask sensitive questions, to tread carefully and sympathise… until I realized that wasn’t actually what they needed. They wanted me to listen, so I grew quiet and listened. I learned to become comfortable with silence, and leave space for them to fill in, leave space for their pain. Most days I returned to my hotel after dark, too overwrought with sorrow and anger to sleep, but alongside the anger also sat admiration and awe. None of the girls I interviewed had both their parents. Many were orphans, their mothers dying of diseases the witch-doctors couldn’t cure and their fathers abandoning them for second and third wives. They lived without running water or electricity. Of the 30 girls I talked to, only 6 were in high school, all of them on scholarships. They lived in concrete boxes in the city’s slums, walking an hour to school on an empty stomach. They did their homework on their laps by the light of the moon and they considered themselves blessed. They were lucky to be learning, they told me. “If you can read and write you can get a good job and you won’t be hungry.” Every bit of knowledge they could wring from their teachers was a step away from the slums. I’d often ask the girls ‘what makes you smile?’ There was so many sad stories, I wanted to know what brought them joy. Books, they told me, and their faces lit up. I didn’t eat lunch the seven days I was there. It felt wrong to pull my sandwich from my bag, when they only ate one meal a day and wouldn’t share mine. I knew this book I had planned to write wasn’t enough to make up for all they’d lost, but, as an author, story was the best way I knew to inspire action, to make people care. Because that’s what books do - especially sad ones - they force us to imagine another person’s pain; to understand, rather than judge, to connect as humans. I left Uganda, with their secrets and dreams in my notebook. I knew hearing their stories was a privilege and that, with that privilege, came a deep and profound responsibility to get the details right, so when I returned to Australia, I continued my research, devouring memoirs and history books, reaching out to professors in Uganda, tribal leaders, teachers and aid workers. It was confronting learning about forced marriages, sexual assault, female genital cutting, domestic violence and the everyday struggles of so many young girls. I almost didn’t write. I almost couldn't. But then, on the page, in the middle of the heartbreak, were small moments of happiness; young girls smiling and stamping their feet to the beat of a drum, starlight, fire light, cousins and clan. And a girl I’d called Lilian drawing letters in the dirt, determined to learn. I was writing during troubling times and that propelled me too. When you’re writing, you’re trying to find answers to things you don’t understand. I didn’t understand how a man who had so little respect for women was elected to run one of the most powerful countries in the world or why women’s rights were being stripped back, and racism was on the rise. All that confusion, anger and fear found a home in Lilian, a girl who wouldn’t be tamed. A girl who spoke out and rebelled in ways I never did. I’d grown up always doing as I was told, doing what was expected. And so, I wrote a book about a girl finding the strength to fight for change, a girl who was afraid, but used her fear to fuel her success. I threw obstacles at her to see if she would make it. I made her stand up and demand what was hers. I wasn’t a particularly assertive or confident teenager, back then we didn’t have the language or framework to tackle inequality, we didn’t have Me too or Michelle Obama and so when my driving instructor made comments about my legs, or the father I babysat for flirted with me, I bristled but did nothing, said nothing. Writing this book for teens about female empowerment, empowered my own teenage self. As a teen I’d never thought of myself as a feminist. I didn’t know who I was or what I stood for and it seemed like such a big statement, so much more than what it is - someone who wants to shape their own life and believes they matter equally. I wanted Lilian to matter equally. I wanted her to find her voice. I didn’t realise in the process I would find mine. I wrote for three years, sending each draft to Namukasa Nusula Sarah, a student I had interviewed on my first day in Kampala. I needed to know I had gotten everything right - how they gripped the cassava when pulling it from the ground, the songs they sang around the fire, the things their aunties taught them so they would be good wives. Namukasa translated words into Luganda and taught me songs. She shared the fables she’d learned as a child and the games she’d played at recess. She sent photos of pit latrines and cooking huts. Yes, she confirmed, teachers sleep with students or yes, my friend who was 13 was married just like that, or yes, the girl in chapter 6 would have spread her legs for a few coins. And then- it was done. It was bittersweet typing those last 2 words - the end. There was pride and relief but also sadness. I’d grown close to my characters, even the ones I’d meant to despise, and then, like children, I had to let them go and send them into the world to be judged, along with my writing. Waiting for first reviews is nerve wrecking, but not nearly as nerve-wrecking as waiting for Namukasa’s verdict on the final draft. I’d sent it to her after making the changes she suggested, and I remember the relief I felt after reading that she had been watching for mistakes but after a few pages had become lost in the story, in her story, and she’d cried, because she was Lilian. She wrote to me: Me and my friends and the girls in my village, everything that happened to Lilian and her friends has happened to one, or all, of us. It’s all there. The lessons and the beatings, the laughter, the drums, the hunger and the fear. I Am Change is a sad story but it’s also a story of hope. The girls I met in Uganda are poor but they are fierce and determined. They don’t need our pity. They will shape their own future, if given the tools. As Namukasa says in her beautiful forward to the book: 'Things can change. Me and my friends will make them change. We just need some help.' I guess, that’s what tonight is about. Change. I wrote this book to offer an alternative vision and add another voice to those who’ve been stifled. The aim in all my books is to reveal to readers worlds they don’t know. With this book it was to have readers look up from the page and be stirred not just to feel something but to do something. You’ll find a phone number on the flyer inside my books where you can donate to Help Girls Learn Uganda, an initiative I set up on my return from Kampala. Money raised will go to the 5 incredible organisations I work with, who save girls from unwanted pregnancies and marriages to older men, feed them when they’re hungry and sit them at desks. We might not have the power to change the world, but we can change one person’s world and bit by bit change entrenched ways of thinking. Things are starting to change in Uganda’s capital. Girls are finishing school and women can choose their own husbands. The change will reach the smaller villages if we continue to make noise and nurture institutions that protect and empower girls so that all girls believe they are worthy of an education; that their bodies are their own and their minds matter. Travel, like literature, is a fantastic educator; another great way to cultivate a deeper empathy and understanding of people whose lives might be different to our own. So, when one of my oldest friends, and co-founder of Executive Edge Travel, Yvonne Verstandig, invited me to co-host a trip to Uganda inspired by my upcoming novel, I Am Change, I jumped at the chance. I would return to Uganda to see the girls who helped shape the characters in my novel, and in turn shape me – as a writer and a person - and spend time with the aid organisations who continue to support them.

I’d seen the difference these organisations made on my last visit; how they’d saved girls from unwanted pregnancies and marriages to older men, fed them when they were hungry and sat them at desks. It’s been such a buzz reconnecting with them to explore how our small group might make a difference. The first leg of the trip will include meeting with female leaders of change, participating in round-table discussions, visiting girls’ empowerment clubs and hearing from young girls about the obstacles preventing them from achieving their dreams - and taking their lead in how we can help them. In between meetings we’ll explore markets, spend time with local artists and fashion designers, watch a witch-doctor at work, drum and dance. Yvonne’s part of the itinerary - a dose of adventure – will take up the last four days and see our small group hike to remote villages, search for game in open top land-cruisers, offer a hand building a mud hut for the local community and trek through the jungle in search of mountain gorillas. If the trip is going to be anywhere near as exciting as the planning of it has been, we’re going to have an amazing 10 days. If you’re free in May 2020 check out the link https://www.executiveedge.com.au/travel-my-way-uganda/ It's been 4 years since I visited Uganda, three and a half years since I tapped the first words of I am Change on my keyboard and saw them pulse onto the screen. I remember how badly I wanted to capture the sticky African heat, the dusty streets and the wide smiles of the girls whose stories I promised to tell. And how nervous I was, waiting to hear Namukasa's verdict after she read an early draft. I needed to know I had sown her experience onto every page. I had drawn on her life and the lives of dozens of other girls who had shared their secrets with me. It couldn’t have been easy letting me into their lives. I asked hard questions and mined their most private and intimate moments and they forgave my ignorance and shared their heartbreak with such warmth and generosity. They told me about forgoing meals to pay for textbooks and trading their bodies for school fees. They told me about the lessons their aunts taught them about their bodies and about men.

None of the girls I interviewed had both their parents. Many were orphans, their mothers dying of diseases the witch-doctors couldn’t cure, their fathers abandoning them for second and third wives. They lived without running water or electricity. A lucky few were in secondary school, on scholarships, the only girls in their class. They lived in concrete boxes in the city’s slums, walking an hour to school on an empty stomach and they considered themselves blessed. They were lucky to be learning, they told me, their faces lit by smiles. “If you can read and write you can get a good job and you won’t be hungry.” I gave them sugar, flour, soap and pencils, but it wasn’t enough. Neither is this book, but it's a place to start. A flint to hopefully spark a desire in you, my readers, to do what you can to help. As Namukasa says in her beautiful forward to the book: 'Things can change. Me and my friends will make them change. We just need some help.' |

Proudly powered by Weebly