- Home

- About

- Inkflower

-

Books & Writing

- Inkflower

- Arabella's Alphabet Adventure

- I am Change

- The Wrong Boy

- Alexander Altmann A10567

- The Tattooed Flower

- Playing for the Commandant

- Hanna Mendels Chans

- La Pianista di Auschwitz

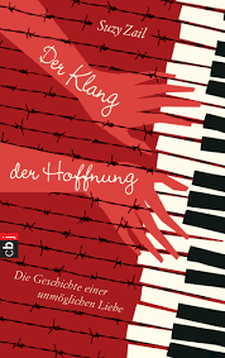

- Der Klang Der Hoffnung

- De Gave Van Hanna Mendel

- Saving Midnight

- Was Dir Bleibt, Ist Dein Traum

- Il Bambino Di Auschwitz

- Smitten

- All You Need is Love

- Pianista De La Auschwitz

- Other Writing

- Author Talks

- Contact

- News

|

Der Klang Der Hoffnung was inspired by my father, both in that it draws upon his experiences in Auschwitz and was written to keep his memory alive. My father had survived Auschwitz as a thirteen year old. He’d never told us what had happened to him in the concentration camp - he arrived in Australia, saw smiling Australian faces and decided the war was an aberration. He put it behind him and started over. It was only after he was diagnosed that he told us everything.

I spent the next five years writing his story and as I watched him live so graciously and bravely with his disease, discovered that I had two stories to tell - how he survived Auschwitz and how he lived whilst dying. The day he died, gathered around his bed with my mother and brothers, I promised to get his story published. I guess I just wanted to put a smile on his face; have him leave us, knowing his story would help others. That book - The Tattooed Flower - was published three years after his death and every time someone reads it I imagine my father up there, somewhere, smiling. I guess that promise - to tell his story – never left me. Or maybe I wasn’t ready to let him go. Writing Der Klang Der Hoffnung allowed me to revisit his story and remember him. It was also the perfect way to pass on his warning never to forget. I didn't choose to write a Young Adult book. The story demanded one. Teenagers are the next generation of leaders. They’re the future and it seemed the perfect audience for a story set in Auschwitz. I knew that the only way to prevent something like the Holocaust from happening again was by trying to understand it and the best way to help kids do that was by giving them a character to care about. Not millions of Jews - just one - a girl or boy their age with the same fears, dreams and insecurities they have. I wrote Hanna, the main character, with my father in mind. Hanna was a teenager, like my father was when he was rounded up and sent to Auschwitz. Both Hanna and my father were brave but perhaps a little naïve - Hanna’s parents hid the truth from her, like my grandparents hid their fears from my father. Both came from loving homes, were visited by guards in the middle of the night and sent to Auschwitz on cattle trains. Both Hanna and my father lost their parents and were separated from their siblings. Both experienced the kindness of non-jews in the camp. But that’s where the similarities end. My father worked on a conveyor belt sorting rocks. Hanna had a chance to escape the quarry through her music. I chose piano because my mother ( a young middle class Hungarian like Hanna) loved music. When I imagined Hanna playing Wagner for the Commander, I only had to think back to my own childhood, sitting on the floor of the piano room in my old house, watching my mother smile as she played Bartok. But Der Klang Der Hoffnung isn’t a book about my parents. It’s about fear, loyalty, love and hate. It's about a tragic moment in history. The characters in the novel are imaginary, but the Debrecen ghetto and the Serly Brickyard, the cattle trains packed with innocent men, women and children, and the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where they were brought to die in the summer of 1944 existed. Dr Mengele stood on the ramp and sent the people who stood before him, to the right or to the left. There was a Commandant of Birkenau, every bit as cruel and sadistic as my Commandant and an Orchestra that were forced to play marches at the camp’s gate. And that weighed heavily on me. I didn’t want to get it wrong, not when it would be read in schools... and read by survivors, so I read history books and watched documentaries. I interviewed survivors and read memoirs and then, after I’d written the manuscript, I sent it to Dr. Bill Anderson, an honorary senior research fellow at Melbourne University and a consultant historian at the Holocaust Centre. I'd also never written fiction before (apart from a few primary school chapter books) so I took a novel class to work-shop my early drafts. It was a steep learning curve, moving from interviewing people to imagining them into existence, giving them a voice and a personality, their own dreams, fears and longings. Having them interact, laugh, cry, love, starve, and sometimes die. Mainly I worried that my plot was believable- that a Jewish inmate could befriend the son of the Camp Commander- that the son of a high ranking Nazi might be kind. And then I met Fred Steiner. It was a few months after I'd finished my book. I was at a literary event (Elliot Perlman was talking about his Holocaust themed book, The Street Sweeper). At the conclusion of the lecture an elderly man raised his hand and asked whether the speaker had ever met a kind German. He wore a short-sleeve shirt, the number the SS had given him a black stain across the white skin of his forearm. He answered before the speaker had a chance to respond. “I have,” he whispered. I found him after the lecture and introduced myself. I asked if he wouldn’t mind meeting me the next day. I wanted to hear his story. In Der Klang Der Hoffnung, I'd made Karl, the son of the Commander, kind and I let him sneak Hanna food. I let them fall in love. I knew it was unlikely that the son of a high-ranking Nazi would defy his father in this way, but I wanted it to be possible. “I tell my story every day at the Holocaust museum downstairs,” the old man said. “Come see me tomorrow.” We met the next day in a small room at the back of the museum. Fred told me that he’d grown up on a farm. That he’d spent his days riding horses, so when the guards at Birkenau asked for inmates to work in the SS stables, Fred put up his hand.He joined Auschwitz’s elite Horse Commando and sometimes when he took the SS officers’ children on pony rides, the men would give him cigarettes which he could trade for food. I asked whether the officers who’d given him the cigarettes were the kind Germans he’d spoken of but he shook his head. “The Commander drove me to his house to chop wood one morning,” he told me. “He left me in the kitchen with his wife. She poured me coffee and fed me cake. She asked for my name. My name,” Fred had smiled. “She used my name.” The Commander had weeks before, whipped Fred until he’d passed out, but his wife had fed Fred cake and given him back his name. It was uncanny. In Der Klang Der Hoffnung, I put Hanna in that same kitchen and I had Karl, the Commandant’s son sneak her cake, but I’d created Karl. The wife of the Commander was real. I don’t pretend to know how it felt to be imprisoned in Birkenau. I don’t think anyone who wasn’t there can ever really understand. But it’s important to try. Reading history books and memoirs, talking about the Holocaust and writing about it is the best way to stop it from happening again. Der Klang Der Hoffnung acknowledges that the world can be a forbidding place, but more than that, I hope it teaches kids that they're capable of great things and that they can help- in big and small ways. |

Proudly powered by Weebly