- Home

- About

- Inkflower

-

Books & Writing

- Inkflower

- Arabella's Alphabet Adventure

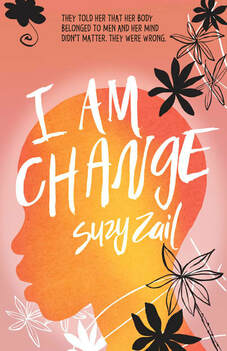

- I am Change

- The Wrong Boy

- Alexander Altmann A10567

- The Tattooed Flower

- Playing for the Commandant

- Hanna Mendels Chans

- La Pianista di Auschwitz

- Der Klang Der Hoffnung

- De Gave Van Hanna Mendel

- Saving Midnight

- Was Dir Bleibt, Ist Dein Traum

- Il Bambino Di Auschwitz

- Smitten

- All You Need is Love

- Pianista De La Auschwitz

- Other Writing

- Author Talks

- Contact

- News

|

Writers are often told 'Write what you know.' In writing holocaust fiction, I’d clung to that rule, drawing on my father’s childhood story and the stories of the survivors I’d grown up with to write my first two YA novels, The Wrong Boy and Alexander Altmann A10567. The 2014 abduction of more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls changed that. The kidnapping haunted me. I wondered what I could do. Not just for the 200 terrified girls held at gunpoint but for the millions of girls scattered around the globe who were being denied an education. And then, by chance, I met Nakamya Lilian, a 29-year-old Ugandan girl visiting Australia. We spent an afternoon together and as soon as she told me her story about growing up in a small impoverished village, desperate for an education, I knew the heart of my next book. But Lilian’s story was only one story, one voice. I needed to learn more, so I flew to Uganda. I didn't know what it felt like to be a poor African girl without shoes or schoolbooks. I needed to speak to girls who did. The best way to do that, I decided, was to contact aid organisations who fought to keep girls in school. I settled on five organisations based in Kampala who advocated for girl’s rights and emailed each of them explaining that I hoped to write a novel about a Ugandan girl struggling to stay in school, but to write an authentic story I needed to meet the girls who lived that story. I told them I had booked a flight to Kampala the following week and was hoping they might introduce me to some of the girls they had helped. I met thirty girls through organisations like Concern for the Girl-Child and Girls Not Brides. I went to their villages, visited their huts, walked to the wells where they gathered water and visited the dusty schools where they learned to speak English until, one by one, they dropped out. They told me about forgoing meals to pay for textbooks and trading their bodies for school fees. They told me about the lessons their aunts taught them about their bodies and about men. Some had been given as wives in exchange for cattle. All of them wanted, more than anything, to learn. I started my days at 8 am, with a line of girls waiting to share their stories. Most days I returned to my hotel after dark, too overwrought with sorrow and anger to sleep, but alongside the anger also sat hope and a deep admiration for the girls I had met. None of the girls I interviewed had both their parents. Many were orphans, their mothers dying of diseases the witch-doctors couldn’t cure and their fathers abandoning them for second and third wives. They lived without running water or electricity. A lucky few were in secondary school, on scholarships, the only girls in their class. They lived in concrete boxes in the city’s slums, walking an hour to school on an empty stomach and they considered themselves blessed. They were lucky to be learning, they told me, their faces lit by smiles. “If you can read and write you can get a good job and you won’t be hungry.” I left Uganda with their secrets and dreams in my notebook. It couldn’t have been easy for them to let me into their lives. I asked hard questions and mined their most private and intimate moments and they forgave my ignorance and shared their heartbreak with such warmth and generosity. I knew hearing their stories was a privilege and that, with that privilege, came a deep and profound responsibility to get the details right, so when I returned to Australia, I continued my research, devouring memoirs and history books, watching movies and you-tube clips, and reaching out to professors and journalists, teachers and aid workers, to amass the knowledge I needed to write an authentic story. I wrote for three years, sending each draft to Namukasa Nusula Sarah, a student I had interviewed on my first day in Kampala. I needed to know I had gotten everything right - how they gripped the cassava when pulling it from the ground, the songs they sang around the fire, the things their aunties taught them so they would be good wives. Namukasa translated words into Luganda and taught me songs. She shared the fables she’d learned as a child and the games she’d played at recess. She sent photos of pit latrines and cooking huts. I remember how nervous I was, waiting for her verdict on the final draft, and the relief I felt after reading that she had been watching for mistakes but after a few pages had become lost in the story, in her story, and she’d cried, because she was Lilian. Me and my friends and the girls in my village - she wrote - everything that happened to Lilian and her friends has happened to one, or all, of us. It’s all there. The lessons and the beatings, the laughter, the drums, the hunger and the fear. I Am Change is a sad story but it’s also a story of hope. The girls I met in Uganda were poor but they are fierce and determined. They don’t need our pity. They will shape their own future, if given the tools. Story isn’t the answer, but it's a place to start. A way to spark action. As Namukasa says in her beautiful forward to the book: 'Things can change. Me and my friends will make them change. We just need some help.' |

Proudly powered by Weebly