- Home

- About

- Inkflower

-

Books & Writing

- Inkflower

- Arabella's Alphabet Adventure

- I am Change

- The Wrong Boy

- Alexander Altmann A10567

- The Tattooed Flower

- Playing for the Commandant

- Hanna Mendels Chans

- La Pianista di Auschwitz

- Der Klang Der Hoffnung

- De Gave Van Hanna Mendel

- Saving Midnight

- Was Dir Bleibt, Ist Dein Traum

- Il Bambino Di Auschwitz

- Smitten

- All You Need is Love

- Pianista De La Auschwitz

- Other Writing

- Author Talks

- Contact

- News

|

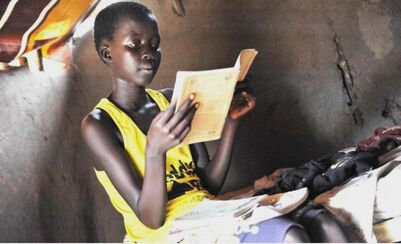

Lilian pulled a book from her bag and cradled the ragged paperback in her hand. “It’s like slipping inside someone’s skin,” she whispered. “You can be anyone. Do anything …” Lilian so badly wanted her father to understand. But how to explain that being in the middle of a story was like being everywhere and nowhere at the same time? - I Am Change Growing up in Australia, I stepped into the magic of stories every day, shedding my skin to try out different lives to test who I might be. In novels I discovered that girls could be heroes. And the more I read the larger my world grew. I had stories to make sense of the universe, atlases to reveal whole continents to me and dictionaries to add to my collection of words. For too many girls in Uganda, books are a luxury. “Books,” they told me, “are more than just things made of paper and ink.” To turn the pages of a book meant gaining a vocabulary. It meant mastery of the English language and that meant a job. Which meant quieting their growling stomachs and paying for their siblings to stay in school. I saw their eyes light up as they turned the pages of picture books and tattered paperbacks. And I saw them hug the books to their chests before handing them back to their teachers. They were used to returning books. “We aren’t allowed to take them home,” they explained. Their classrooms and school libraries - if their school had a library - were often almost empty, the books too few to be given out on loan. I didn’t ask if they could afford to buy books; they couldn’t afford lunch. And they were the fortunate ones, the girls who were still in school and hadn’t been married off. Of the thirty girls I met in Uganda in 2015, only six had made it to high school, all of them on scholarships. Most were orphans. They lived in concrete boxes in the city’s slums, walking an hour to school on an empty stomach and they considered themselves blessed. They were lucky to be learning, they told me. “If you can read and write you can get a good job and you won’t be hungry.” Every bit of knowledge they could wring from their teachers and from books was a step away from the slums. I asked the girls what made them smile. There was so many sad stories, I wanted to know what brought them happiness, because they were so much more than poor. They were fierce, determined, warm and generous. And they were hungry to learn. “Light bulbs,” they told me. “A second pair of underwear. A pair of shoes.” But mostly it was books. Books were their escape, not just from a difficult day, but from a hard life. I talked to girls who walked through the bush to get to school, risking sexual assault and their rejection of their families; girls who sat cross-legged on the dirt floors of their classrooms while their brothers sat at desks; girls who sold their bodies for textbooks and washed their neighbours’ clothes to pay for excursions. Reading wasn’t just about being transported to a different time and place. For the girls in the slums and villages of Uganda, books were their ladder out of poverty, a passport to a better life. Because it’s hard to escape abuse if you can’t read and write. So what can we do? We can give girls books. When I posted #giveagirlabook on @authorsuzyzail a few months ago, calling on people during Book Week to spare a thought for the millions of girls who dream of owning a book, the response was impassioned and immediate. People wanted to give their pre-loved books to girls who couldn’t afford them. I just had to find a way to get their books to Africa. And that’s when I discovered Australian Books for Children of Africa, a non-profit organisation who ship books to impoverished schools. To date, they’ve sent over 250,000 books to empower children through education. And now that we’ve teamed up with them, we can get girls in Africa precious picture books, novels, dictionaries, history books and atlases. Click HERE to find out how to donate your new or second hand books to girls who can’t otherwise afford them and mention #giveagirlabook to earmark your donation for girls in need. Those books your kids read that they’ll never re-read? Donate them. The childhood books you keep boxed up in the garage because you can’t bring yourself to throw them out? Let a girl in Africa turn the pages in wonder as you once did. If you’re a member of a local library, find out what they do with their old books. Your child’s school? They have to cull their library collection every year. Send them the link. We might not have the power to change the world, but we can change one person’s world…starting with a book.

3 Comments

AUTHORS EMPOWERING GIRLS: WE SPEAK WITH SUZY ZAIL, AUTHOR OF 'I AM CHANGE' Welcome to the second interview in our 'Authors Empowering Girls' series! We love empowering books for girls so much that we're speaking to the amazing authors who wrote them. This month we're speaking with the multi-talented Suzy Zail, young adult author, about her empowering new book 'I Am Change'. Read Suzy's incredible story below and be inspired by all the amazing work she is going to empower girls around the world. Thanks Suzy! What's the name of your book and what's it about?‘I am Change’ is the sad but empowering story of a young Ugandan girl’s struggle to stay in school. I wrote the book in collaboration with the many girls I interviewed while on a research trip to Uganda in 2015. The heartbreaking and intimate stories they shared have all made their way into this book about a girl who refuses to shrink herself to fit other people’s idea of what a girl is. In Lilian’s small village a girl isn’t meant to be smarter than her brother. A girl is meant to go to school, or enjoy her body or decide who to marry. Especially if she is poor. Tell us a bit about yourself and how you got into writing.I have always been interested in people. When I left school, I wanted to be a psychologist but my father thought Law would be a safer option. Safe is important when you’ve seen the inside of a concentration camp. I completed my degree and practiced for six years specializing in family law but then, in 1998, my father was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease and given 6 months to live. I quit. Life was too short to do something I wasn’t passionate about. I didn’t know what I wanted to be; I just knew that I wanted to spend time with my father. And he wanted the same thing. He didn’t want to waste the little time left to us crying, he wanted to talk and the first thing he wanted to tell us was his life story, so he flew the family to Fiji where we spent 9 nights, over 25 hours, listening to his story. We knew he’d survived the Holocaust as a child, but didn’t know what he’d seen in the camps. We knew he’d lost his parents and brother but he’d never told us how. He told us everything, and his openness in allowing us to share every aspect of his life and later his illness, was the greatest gift he gave us. He told us about his early years, being beaten up at school, the yellow armband, the trip in the cattle train to Auschwitz and his first experience seeing death. He told us about being separated from his sisters, mother, then father and brother. My father hadn’t told us these things because they weren’t part of his new life in Australia, with us. He’d decided after coming to Australia in 1950, that the war had been a bleak time in history and that people were, in the main, good and kind. So he disconnected from the past as a way of moving forward. But now he was dying and it was time to look back…. The 6 months turned into 5 years and watching my father use the time left him as an opportunity to deepen his relationships and grow as a person, I knew I had to pass on the lessons I’d learned while watching him die. Writing his story, The Tattooed Flower bound us together. It also helped make sense of his illness. There had to be some point to my dad dying, some upside. The upside is we parted friends. The upside is I knew his favourite colour and what he dreamed about at night. And then, just before he died, I promised I’d get his book published. I had no idea how to write, at least not creatively, so I went back to university and studied professional writing and editing at RMIT. A year later I sent my father’s story to a publisher and that was the end of my law career and the beginning of my writing life. What made you want to write an empowering book for girls?I think it was fear that drove me. I started thinking about writing a book about girls’ rights around 2014 after Boko Haram, a terrorist organisation opposed to girls’ education, abducted more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls. The kidnapping haunted me. I wondered what I could do. Not just for the hundreds of terrified girls, but for the millions of girls around the globe who were being denied an education. And then, by chance, I met Nakamya Lilian, a 29-year-old Ugandan girl visiting Australia. As soon as she told me her story about growing up in a small impoverished village, desperate for an education, I knew the heart of my next book. But Lilian’s story was only one story, one voice. I needed to learn more, so I flew to Uganda. I didn't know what it felt like to be a poor African girl without shoes or schoolbooks. I needed to speak to girls who did. I interviewed thirty girls through organisations like Concern for the Girl-Child and Girls Not Brides. I went to their villages, visited their huts, walked to the wells where they gathered water and visited the schools where they learned to speak English until, one by one, they dropped out. They told me about forgoing meals to pay for textbooks and trading their bodies for school fees. They told me about the lessons their aunts taught them about their bodies and about men. All of them wanted, more than anything, to learn. It was confronting learning about forced marriages, female cutting, domestic violence and the everyday struggles of so many young girls. But then, in the middle of the heartbreak, were small moments of happiness; young girls smiling and stamping their feet to the beat of a drum, starlight, fire light, cousins and clan. And these brave, fierce girls, determined to learn. I knew this book I was planning to write wasn’t enough to make up for all they’d lost, but, as an author, story was the best way I knew to inspire action, to make people care. Because that’s what books do - especially sad ones - they force us to imagine another person’s pain; to understand, rather than judge, to connect as humans. I didn’t know how I would trap everything I’d learned in that complicated, beautiful place in the pages of a novel but I was determined to try. I was writing during troubling times and that propelled me too. When you’re writing, you’re trying to find answers to things you don’t understand. I didn’t understand how a man who had so little respect for women was elected to run one of the most powerful countries in the world or why women’s rights were being stripped back and racism was on the rise. All that confusion, anger and fear found a home in Lilian, a girl who wouldn’t be tamed. A girl who spoke out and rebelled in ways I never did. I’d grown up always doing as I was told, doing what was expected. And so, I wrote a book about a girl who was afraid, but used her fear to fuel her success. I threw obstacles at her to see if she would make it. I made her stand up and demand what was hers. I wasn’t a particularly assertive or confident teenager, back then we didn’t have the language or framework to tackle inequality, we didn’t have Me too or Michelle Obama and so when my driving instructor made comments about my legs, or the father I babysat for flirted with me, I bristled but said nothing. Writing this book for teens about female empowerment, empowered my own teenage self. As a teen I’d never thought of myself as a feminist. I didn’t know who I was or what I stood for and it seemed like such a big statement, so much more than what it is - someone who wants to shape their own life and believes they matter equally. I wanted Lilian to matter equally. I wanted her to find her voice. I didn’t realise in the process I would find mine. What are your thoughts on strong female characters in books?Love them. And part of the reason I wanted to write about a strong Ugandan girl was so the girls I had met could read about a girl like them. The only books many of them had, if they could afford books at all, were fairy-tales about white-skinned princesses with straw-coloured hair who wore ballgowns and glass slippers. They wanted to see their lived experience on the page and be inspired by girls who had to wake at 4 am to wash the neighbours’ clothes so they could afford to pay school fees. What does girl empowerment mean to you?It means different things depending on where and how you live, but for me it means being able to shape your own life. It means having the right to make decisions about your body, your career and who you live with. It means having equal rights and being encouraged to dream big. And always believing that you matter equally. What's next for you and where can we follow your work?I Am Change has just hit bookshelves so I’m in the process of promoting it - doing talks at schools and trying to raise awareness – and funds – for girls’ empowerment and education. The aim in all my books is to reveal to readers worlds they don’t know. With this book it was to have readers look up from the page and be stirred not just to feel something but to do something. So, on my return from Uganda I set up Help Girls Learn Uganda, an initiative to raise money for the 5 incredible organisations who support the girls who shared their stories with me. I’m also working on a more recent initiative ‘Give a girl a book’, which I launched on Instagram, so I’m busy setting up ways to get books into the hands of girls who need them, whether they be textbooks, picture books or novels. I’m also itching to get started on another novel… and waiting for inspiration to strike. You can connect with me on my website, or follow me on Instagram. You can check out Suzy's fantastic book 'I Am Change' on Amazon or Booktopia. |

Proudly powered by Weebly