- Home

- About

- Inkflower

-

Books & Writing

- Inkflower

- Arabella's Alphabet Adventure

- I am Change

- The Wrong Boy

- Alexander Altmann A10567

- The Tattooed Flower

- Playing for the Commandant

- Hanna Mendels Chans

- La Pianista di Auschwitz

- Der Klang Der Hoffnung

- De Gave Van Hanna Mendel

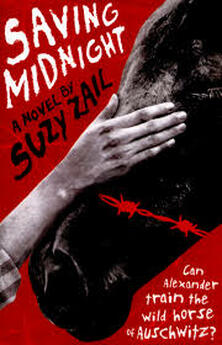

- Saving Midnight

- Was Dir Bleibt, Ist Dein Traum

- Il Bambino Di Auschwitz

- Smitten

- All You Need is Love

- Pianista De La Auschwitz

- Other Writing

- Author Talks

- Contact

- News

|

Every book has a backstory. Saving Midnight began in 2012 in a lecture hall at the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne. At the conclusion of the lecture an elderly man raised his hand and asked whether the speaker had ever met a kind German. He wore a short-sleeve shirt, the number the SS had given him a black stain across the white skin of his forearm. He answered before the speaker had a chance to respond. “I have,” he whispered.

I found him after the lecture and introduced myself. I asked if he wouldn’t mind meeting me the next day. I wanted to hear his story. I’d just finished writing, The Wrong Boy, a story about Hanna, a Jewish girl in Auschwitz who befriends the son of the Camp Commandant. I wanted the boy – Karl - to be nothing like his father. I made him kind and I let him sneak her food. I let them fall in love. I knew it was unlikely that the son of a high-ranking Nazi would defy his father in this way, but I wanted it to be possible. “I tell my story every day at the Holocaust museum downstairs,” the old man said. “Come see me tomorrow.” We met the next day in a small room at the back of the museum. His name was Fred Steiner and he told me that he’d grown up on a farm. That he’d spent his days riding horses, so when the guards at Birkenau asked for inmates to work in the SS stables, Fred put up his hand.He joined Auschwitz’s elite Horse Commando and sometimes when he took the SS officers’ children on pony rides, the men would give him cigarettes which he could trade for food. I asked whether the officers who’d given him the cigarettes were the kind Germans he’d spoken of but he shook his head. “The Commander drove me to his house to chop wood one morning,” he told me. “He left me in the kitchen with his wife. She poured me coffee and fed me cake. She asked for my name. My name,” Fred had smiled. “She used my name.” The Commander had weeks before, whipped Fred until he’d passed out, but his wife had fed Fred cake and given him back his name. It was uncanny. In The Wrong Boy, I'd put Hanna in that same kitchen and I had Karl, the Commandant’s son sneak her cake, but I’d created Karl. The wife of the Commander was real. We ended up meeting five or six times in that room at the back of the museum. Saving Midnight is inspired by the story Fred Steiner told me over the following months. Some of what happened to the fictional Aleksander Altmann, happened to Fred. Fred cared for the Commander’s horse and survived on handfuls of hay and stolen sugar cubes. But the boy I created is nothing like the fourteen-year-old Fred who stepped off the cattle train at Auschwitz and nothing like the generous, warm man who told me his story two years ago and allowed me to re-imagine it. The Alexander I typed into existence avoided any overtures of friendship from his room-mates. He didn’t share his secrets, or his food. He thought that to care for others was dangerous and to feel, cry or grieve was weak and would get him killed. He closed himself off from his fellow prisoners because he’d convinced himself that was the best way to survive. I wanted Alexander to shun others because I wanted to tell a story about a damaged horse and a lost boy who heal each other. I wanted the war to change Alexander. I wanted him to learn to trust others, to offer help and accept it in return. I wanted him to make himself vulnerable and understand that making yourself vulnerable takes great strength. And that life without connection is meaningless. Tapping into a fourteen year old girl’s emotions to write Hanna Mendel’s character in The Wrong Boy wasn’t difficult. I’d fallen in and out of love and I’d lost a parent. I had my father’s stories about the camps to draw on and memories of sitting on the floor as a child and watching my mother play piano. Inhabiting Alexander Altmann, a tough, angry, emotionally shut down 14-year-old boy was harder. And then...horses. If I was to be Alexander I had to know what it felt like to run my hands over a horse's soaking muzzle. I had to know what it felt like to climb onto a stallion’s back. I had to know a halter from a lead line and the horse’s poll from its hocks. I’d only every sat on a horse a handful of times as a child, and never comfortably. No-one would believe Alexander was an expert with horses unless I became one. I borrowed horse books, watched videos and read training manuals. My friend, Lisa introduced me to her horses, Isabella and Reily and let me dip my fingers into their feed bins and wash the mud from their feet. My research lasted for weeks that turned into months and when I started to write I found myself back at the computer screen, returning to the images of black stallions and copper-coloured ponies, sometimes opening a book or clicking on a website halfway through a scene, sometimes mid-sentence. I’d leave Alexander in the hot sun, hungry and tired, and google horse-feed or leave the Commander barking orders to type how to tame a wild horse into a search engine. Like Alexander, the horses allowed me to escape the darkness of Auschwitz. They were a respite for both of us. I won’t reveal the end of the book but Fred’s story had a happy ending. He survived the war and made a new life in Australia. He married and had three children. He was finally safe, but he didn’t sleep well. The nightmares stopped only when he became a guide at the Holocaust museum and started talking about his experience.old me he continued to worked as a guide at the Holocaust museum because it kept the nightmares at bay and because he knew that talking about the Holocaust was the best way to stop it from happening again. Fred has now passed away but I know he would take pride in the fact his story is still being told and that, together, through story, we are trying to keep the past from fading and to heed my own father’s warning never to forget. |

Proudly powered by Weebly